In Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Moderna, Inc., No. 23-2357 (Fed. Cir. June 4, 2025), the Federal Circuit affirmed a claim construction that doomed Alnylam’s infringement case against Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine. The decision reinforces the primacy of clear definitional language in a patent’s specification—even when it narrows claim scope beyond what a patentee may have intended.

Background: The mRNA Lipid Dispute

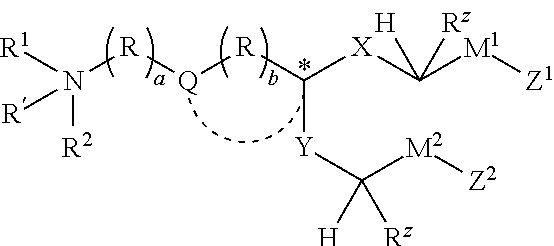

Alnylam sued Moderna, asserting that the SM-102 lipid in Moderna’s SPIKEVAX® vaccine infringed U.S. Patent Nos. 11,246,933 and 11,382,979. The patents concern cationic lipids used for delivering nucleic acids into cells, particularly formulations where the hydrophobic “tail” includes a “branched alkyl” group.

The litigation hinged on the meaning of the claim term “branched alkyl.” Moderna prevailed on a noninfringement stipulation after the district court adopted a narrow construction based on a definitional sentence in the patents’ shared specification.

The Disputed Definition

The critical passage appeared in the “Definitions” section:

“Unless otherwise specified, the term ‘branched alkyl’ … refer[s] to an alkyl … group in which one carbon atom in the group (1) is bound to at least three other carbon atoms and (2) is not a ring atom of a cyclic group.”

The district court treated this as lexicography and rejected Alnylam’s attempt to use a broader “plain and ordinary meaning” interpretation. Because Moderna’s lipid did not include a carbon atom meeting the “bound to at least three other carbon atoms” requirement, the court granted judgment of noninfringement.

Federal Circuit Analysis

The Federal Circuit affirmed, holding that the passage was definitional under the standards set out in Vitronics Corp. v. Conceptronic, Inc., 90 F.3d 1576 (Fed. Cir. 1996) and its progeny:

- The term was in quotation marks, signaling definition.

- It was introduced with “refer to,” which courts have consistently viewed as definitional (ParkerVision, Inc. v. Vidal, 88 F.4th 969 (Fed. Cir. 2023)).

- It was placed in a section titled “Definitions,” supporting the lexicographic reading.

- The specification used permissive phrasing elsewhere (“e.g.,” “include”), contrasting with the precise language used for “branched alkyl.”

The panel also rejected Alnylam’s fallback argument that its claims fell under the “unless otherwise specified” exception. The court held that this clause required a clear, specific departure—and nothing in the claims, specification, or prosecution history met that bar. References to secondary carbon structures in dependent claims and the prosecution record did not rise to the level of an explicit override of the express definition.

Key Cases Cited

- Vitronics Corp. v. Conceptronic, Inc., 90 F.3d 1576 (Fed. Cir. 1996): A patentee may define terms, but must do so clearly.

- Bell Atl. Network Servs., Inc. v. Covad Commc’ns Grp., Inc., 262 F.3d 1258 (Fed. Cir. 2001): Lexicography requires “clearly set forth” intent to redefine.

- Merck & Co. v. Teva Pharm. USA, Inc., 395 F.3d 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2005): Definitions in specifications carry strong weight.

- Thorner v. Sony Computer Entm’t Am. LLC, 669 F.3d 1362 (Fed. Cir. 2012): Terms set off in quotes and defined with “refer to” language support lexicography.

- ParkerVision, Inc. v. Vidal, 88 F.4th 969 (Fed. Cir. 2023): Use of “refer to” supports definitional intent.

Takeaway

This case is a strong reminder that express definitions in a patent’s specification—especially when found in a “Definitions” section and marked with formal language—will bind the claim scope unless there is a clear and unmistakable reason to depart. Practitioners should be cautious with language like “unless otherwise specified” unless they can point to explicit exceptions elsewhere in the specification or prosecution history. Ambiguities or broader examples won’t suffice to override precise definitions.