In a recent decision, Ingenico Inc. v. IOENGINE, LLC, the Federal Circuit upheld a jury’s finding that several claims of IOENGINE’s U.S. Patent Nos. 9,059,969 and 9,774,703 were invalid due to anticipation and obviousness by publicly available prior art. Specifically, the Court affirmed that a software application known as the “Firmware Upgrader,” part of M-Systems’ DiskOnKey System, constituted prior art under the “public use” provision of 35 U.S.C. § 102(b) (pre-AIA).

Background

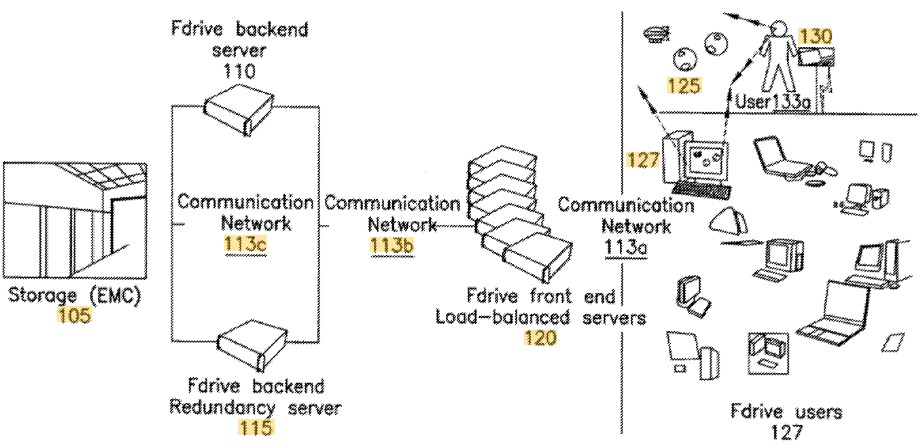

IOENGINE’s patents relate to portable devices, such as USB thumb drives, that send communications to network servers upon user interaction. Ingenico challenged the validity of IOENGINE’s patents by demonstrating prior public use of M-Systems’ DiskOnKey System, including its Firmware Upgrader software.

At trial, Ingenico presented significant circumstantial evidence of the Firmware Upgrader’s public accessibility before the critical date. Evidence included a July 2002 email to M-Systems employees encouraging dissemination of the Firmware Upgrader and associated documentation, a public press release, and archived web pages from which the software could be downloaded.

Court Analysis and Key Precedents

The Federal Circuit’s analysis emphasized two important precedents:

- Medtronic, Inc. v. Teleflex Innovations S.A.R.L. (2023) clarified that circumstantial evidence is equally persuasive and sufficient compared to direct evidence for proving public use.

- Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing Co. (3M) v. Chemque, Inc. (2002) was distinguished due to the lack of evidence in 3M demonstrating that samples provided were ever used in a manner fulfilling claim requirements.

In contrast to 3M, Ingenico demonstrated clear evidence that the Firmware Upgrader software was publicly accessible and encouraged for use, meeting the claims’ criteria once downloaded. Thus, circumstantial evidence was adequate to satisfy the public use requirement.

Clarification on IPR Estoppel and Jury Instructions

IOENGINE argued for a new trial, asserting improper jury instructions regarding conception, diligence, public use, and sales offers. It also challenged the district court’s decision allowing Ingenico to rely on prior art under IPR estoppel provisions.

The Federal Circuit rejected these arguments, holding that the jury was properly instructed on the clear and convincing evidence standard and other critical issues. Additionally, the court clarified the scope of IPR estoppel under 35 U.S.C. § 315(e)(2), holding that estoppel does not extend to grounds involving public use or on-sale bar evidence because these grounds cannot be raised in inter partes review, which is limited to printed publications and patents as prior art.

Conclusion

The decision underscores the importance of demonstrating prior art’s public accessibility through circumstantial evidence. Additionally, it offers crucial guidance on the limits of IPR estoppel, affirming that petitioners are free to assert public use and on-sale bars in district court actions despite participating in an IPR. Patent holders and challengers alike must carefully consider the implications of public availability and IPR proceedings in shaping their litigation strategies.

By Charles Gideon Korrell